“Mr. Wondra, could you read this to make sure I’m doing this right?”

“Sure.” I knelt down at her side.

“Autumn. Do you have any examples from your life in this?”

“No.”

“Did you decide whether you agree with your sign or not?”

“No.”

“Does your introduction include a story?”

“No.”

I think it was at this point that I noticed she was crying.

In the past, this would have baffled me. In this post, I’m going to discuss why Autumn was crying. But first I’d like you to consider the following research. Trust me, we’ll get back to the drama between Autumn and Mr. Wondra shortly.

In 1991, Janel Caine, a graduate student at the University of Florida, set out to design a study to determine if playing music to premature babies might lead them to improved appetites and faster growth. What she found was interesting: babies exposed to soft music in their cribs did grow faster, had fewer complications, and were discharged home from the hospital an average of five days sooner than babies that were not exposed to music.

That data alone has far-reaching and potentially powerful implications, but when you break her findings down by gender (which, surprisingly, she doesn’t do in her paper), they become truly startling.

Baby girls exposed to music left the hospital an average of nine and a half days sooner than babies that were not. Baby boys exposed to music left no sooner at all!

Why? A number of recent studies measuring the “acoustic brain response” of boys and girls has documented that girls hear “substantially” better than boys—“especially in the 1,000—4,000-Hz range.” (Sax)

Again, interesting data. But these findings become even more significant when linked with research documenting that the range of sounds around 1,500 Hz is critical for understanding speech.

All this helps to explain why, on average, girls pick up language skills sooner than boys. But does this head start give girls an advantage throughout their years in school? And what can we, as teachers, do about this?

We’ll get into what this all means for language skills in a minute. But first, I’d like to discuss what this new information might mean for how our students experience the classroom environment.

If it is indeed true that girls can hear certain tones related to speech “significantly better” than boys, I’m going to want to keep that in mind when planning my seating arrangements. I may want to avoid placing a girl near the door. If someone is talking in the hall, she’ll have a greater chance of hearing it and being distracted. On the other hand, since I often give instruction from the front of the room, and know boys don’t hear as well, I may want to seat them near the front. Being a male myself with a voice that projects, I may also want to avoid seating girls in front or they may think I’m shouting. This might also have implications for oral reading.

As a man, with a voice that carries, I also want to keep this information in mind when addressing girls individually. If I use my normal tone, she might think I’m yelling at her. In fact this is exactly what happened the other day with Autumn in the computer lab.

Because girls hear certain tones much clearer, often times, depending on a teacher’s tone, a boy will have trouble hearing it, and a girl will hear it as loud. This has implications for both male and female teachers.

Women with softer voices may want to project a bit more for the boys. Men with low booming voices may want to tone it down a bit so as not to overpower the girls. Teachers are presenters, and so we should reflect on the tone and volume of all our auditory instruction—not only our speech, but also any audio we present.

This also has implications for one-on-one communication—as illustrated in the example at the start of this post. In the end, I told Autumn that I knew why she was crying, that I wasn’t angry, and I apologized for being loud. When I toned it down, we began again and made progress on her paper.

The Anatomy of Aptitude

If you begin reading the literature on gender differences, it won’t take long before you stumble upon a book entitled Brain Sex: The real difference between men and women, by a couple of researchers by the names of Anne Moir and David Jessel. Published in 1991, this was one of the first serious brain-based looks at the difference between sexes. One of Moir and Jessel’s thematic premises is that innate differences in the biological brains and anatomy of children lead them naturally to different interests, which in turn strengthens that aptitude. For example, they contend that girls learn language at an earlier age than boys because their brains are more efficiently organized for speech. Then, since they are able to use language earlier, they do–playing and practicing their way to ever higher levels of proficiency–while boys don’t–which compounds any perceived language deficiency.

Cain’s study, combined with the growing scientific brain and sensory research indicating that girls hear better, leads us to the conclusion that girls are naturally better equipped at an earlier age to learn language.

It makes sense that girls would typically use language more often as they mature. In fact, observation proves this.

It makes sense that girls would typically use language more often as they mature. In fact, observation proves this.

Girls on the playground use more language in their play–working out who will roleplay what relational role, (“Ok, this time you be the mommy and I’ll be the baby . . .”). Boys, on the other hand, are more often content making engine noises (trucks, cars, planes, backhoes), pushing things through the dirt, or throwing things through the air–crashing, chasing, tumbling, and kicking things around.

As Moir and Jessel point out, because language (both reading and speaking) is learned more through sound than sight–when it comes to learning to speak and read:

. . . the structure of the female brain gives girls the advantage. This learning function resides in the left hemisphere of the brain . . .their more natural female strength, which is hearing, not seeing (62).

They go on to support this finding by citing studies that indicate that while boys are better at identifying animal noises, girls are better at identifying human, social, and verbal communication.

It is neither the relative immaturity of boys, which results in their being (less able to read), nor is it that they are backward, though much educational damage has been done in the past by the assumption that a boy’s slowness in learning to read must be due to stupidity or laziness. It is just that while the girls are using the right tool for the job—the “hearing” skills—the boys are better endowed with the skills of seeing, not hearing. And that’s not a good way of learning to read, says American psychologist Dianne McGuinness:

“It is clear that visual processing has little to do with reading, and in fact a strong reliance on the visual mode is often antagonistic to progress in learning to read.”

What does this mean for my eighth grade language arts class?

All that is well and good. But I wanted to test some things out in my own classroom. To my way of thinking, if all the above is actually true, by the time my students hit 8th grade, the average boy should have read significantly fewer books than the average girl.

So I had all my students sign up for a Shelfari account–listing every book that they could ever remember reading. Next, I simply had them tally the books up. The data was striking. On average, girls listed 52 books. Boys listed 25.

The next set of data I collected was from a Reading Interest Inventory. My student’s answers to two questions from that survey were particularly striking:

On a scale of 1 to 10 where 10 is extremely important and 1 is not at all important:

- How important is reading to you? and,

- How important is reading to the world?

In both cases, girls valued reading more than boys.

Intrigued, I went on to have my students complete a survey in which students rated themselves according to Howard Gardner’s Multiple intelligences. I was interested in how boys rated themselves in regard to the Verbal/Linguistic intelligence compared to girls.

As it turns out, of all the intelligences I measured, the greatest average difference was the Verbal Intelligence.

On a scale of 0-100, boys scored themselves at an average of 29.71—the lowest ranking of all the intelligences, while girls ranked themselves at 45–somewhere in the middle.

There were a couple of other interesting data points from my survey that showed up and are supported in the literature on gender differences:

- Boys rated themselves higher in logical intelligence,

- Boys’ viewed their highest intelligence as kinesthetic.

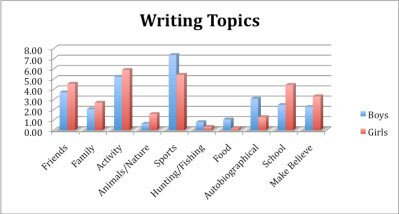

If you read the literature, all this makes sense, which might also explain why boys also wrote about sports in their daily journals more than any other topic.

For reasons I’ll have to write about later, the literature also supports the idea that boys would write in a more autobiographical nature than girls. Girls also wrote more often about “school,” “friends,” and “family” than boys did.

So Now What?

So what does all this mean for teachers? Simply put, we need to understand.

Interestingly, in his article, Getting Boys to Read, Jeff Wilhelm says that, “The reason certain text types (like nonfiction) and features of texts (visuals) tend to engage boys has much less to do with the text itself, and much more to do with the connection (my italics) these features encourage the readers to make to the world.” Wilhelm goes on to list a number of features and conditions that contribute to boys being able to engage in their reading:

- Short

- Visual

- Challenging

- Edgy

- Real

- Current

- Humor

- A clear purpose and immediate feedback

- An appropriate challenge and assistance to meet it

- Functionality and a developing sense of competence

- A focus on the immediate experience

- The importance of being social

I agree, but when it comes to gender differentiation in the classroom, there is a lot more that can be done. Stay tuned. In coming weeks I’ll share with you some ways you can use gender differentiation to increase student engagement in your classes.

For now, however, let me ask you: What differences do you notice between how boys and girls learn in your classes?

Homepage image credit

Designed by

Designed by

Pingback: Listen up! Boys and girls hear, learn, read differently | We Teach … | girls

Chris,

This post has given me a lot of food for thought. I thought high school English language learners from various countries for a long time! They were in a boarding program. I was wondering how culture might impact this process.

Hi Shelly,

Thanks for the comment and visit. The scientific literature about brain and sensory differences is really opening some eyes about how we should be looking at teaching and learning.

Chris

This is a great article which only begins to identify the differences between boys and girls – particularly how they perceive their environment and how they learn. I touched upon students’ individual differences in my blog post http://blog.sharedschool.com/?p=182, and Chris breaks it down by gender here. Simply put, our students have different learning styles and learning paces and a “one size fits all” approach might be fine for the majority, but detrimental for many others. In the spirit of leaving no child behind, we need to think outside of the box.

Hi Cliff,

You’re right. This article only scratches the surface when it comes to explaining the reality about how boys and girls are different. Lots and lots of new research is emerging. My plan is to write more on this topic very soon.

Thanks for the visit and taking the time to leave your thoughts.

Wow, great work! This brings back grad school memories! I sure miss our crew. You did an amazing job on this!

Love the research and application thereof.

Thanks Pam,

Chris

Great article. I found it fascinating.

From a former student,

Sam

Thanks so much for the great information-using it for my report!